|

Grave and Gay by Louise

McKay

The Flanagan Girls Old-Time Memories

The Irish Novelty House, Bridge Street, Belfast

Author of "The Mountains of Mourne" "A Little Bit of Ireland" etc.

Printed by McCaw, Stevenson and Orr, Limited, The Linenhall Works, Belfast

Foreword - I have been asked from time to time to publish Memories of Older

Times - and The Flanagan Girls, a humorous tale of life in the country

to-day. In presenting these varying descriptions of country life of to-day

and yesterday to my readers, I hope that some memory however slight, may be

recalled. - Louise McKay

The Flanagan Girls

Many's the one has said to me, "Did

ivir ye come across the Flanagan girls?" but the divil an eye ivir I

clapped on one or other of them till the night of Teggarty's party.

For sure they were well worth havin' a squint at - well worth the five long

Irish miles I traveller over mountain an' bog, jist to have it to say I had

seen the Flanagans. They were twins; an' bad t'ime if I could tell one

from the other. Oul' Biddy Tierney (a neighbour of mine) said to me

time an' again, "Paddy, don't marry till ye see the Flanagan girls."

(Biddy knowed I had a strong notion of marryin'.) So there I was,

sittin' in Teggarty's barn where the dancin' took place, for no other reason

than to see the Flanagan girls. Right enough, there was ivirything

about them to take a man's fancy; so I looked at one an' then at the other.

"Which of them is it to be?" sis I to m'self; "I think I'll try

the wee one; she's a sonsy-lookin' bit of goods." So over I goes, an'

sis I to her (the wee one), "Will ye be my partner, miss?" I meant, of

coorse, my partner at the dance. At that remark, instead of answerin'

me, she an' the other one giggled an' laughed, an' at the same time got up

to their feet, an' I'm blist if they weren't both the same height, an'

whativir way they manoeuvred I couldn't tell which of them I had put the

spake on. "I beg pardon," sis I to the one nearest me, "will ye

dance with me?" "You asked my sister that question jist now," sis she.

She spoke with an English accent, an' she, to my own knowin', reared an'

lived all her day at Skelty's bog. "Troth maybe I did," sis I.

Not to be outdone I attacked the other one with the same question.

"Oh, certainly," sis she; an' while I looked roun' for a seat for her

they had changed places again, an' the divil a bit of me knowed which was

which. Howanivir, after they had confabbed together for a while, one

of them came forward an' offered to give me the first dance; I could

see they wanted to have a shine out of me. No doubt they thought me an

ignorant chap that couldn't dance, but I could tell tham I was two winters

at Phil McGladdery's dancin' class; I wasn't such a clown as they took

me for, so I put on my best manners: "Allow me, miss," sis I, as

I offered her my arm. There was a polka goin' on at the time, an' that

was the one dance I was a master-hand at; so as we futed it roun' an' roun'

she drawled out, "I'm not used to dancin' polkas; they're quite

out-of-date," an' added, "I wish they'd give us a fox-trot."

Now I nivir heard word of that trot; maybe she did at Skelty's bog.

Folk said there was fairies at Skelty's bog - maybe they learned her. Her

nixt remark was, "I wonder could I have an ice?" Well she knew that ye

might as well look for a needle in a hay-stack as ask for ices at Teggarty's.

By this time we were seated, an' I could see her sister an' herself

exchangin' looks an' laughin' for all they were worth. There was

others in the plot as well; it was easy seein' I was the clown of the evenin',

but I took my time; I wasn't as green as I looked. "Have a cigarette,"

sis she, as she took a case out of a bag business she had tied to her waist.

"Have a cig," she repeated in a drawly kin' of voice that she nivir learned

at the bog side; "they're a good brand." Her nixt move was to strike a

match on the heel of her shoe an' light the same cigarette with an air of

freedom as is she was London born. Iviry eye was on us. "There

goes the Blue Danube," sis she; let's have a waltz." I noticed her

sister got up to dance jist then with what seemed to me to be a polisman all

dressed up. They kept noddin' an' winkin' at my partner. Sis I

to m'self, "I've had enough of this; they'll be makin' a ballad on me if I

stay here any longer. The Flanagan girls may go to blazes for all I

care." So when she asked me to waltz, I jist said, "Excuse me,

miss," an' I walked straight out. As I said, I walked out, an' went

into Teggarty's haggard an' had a smoke there; I wanted to cool my temper.

After a while I slipped into the barn again. The dancin' was in full

swing, an' the first one I saw was my partner dancin' with another polisman.

"Good luck t'ye," sis I to m'self; "I don't grudge ye to him."

There was "wallflowers" aroun' lookin' on, so I went over an' sat down

beside an oul' acquaintance, Susy Trimble. Now I knowed for a long

time that Susy had a great wish for me, an' in troth maybe I had one for

her, but Susy was lame, besides she was miles oulder than me - I mean she

was a wheen of years ahead of me - all the same I always looked up to her.

Only for fear of what the people would say, I would have went in for Susy

long ago. What people would say has kept many's the one back; an' sure

if iviry one knowed or heard what iviry body else was sayin' about them,

there would be a civil war; iviry one would be tearin' other people's hair

out. It would be a war bigger than the Great War. I listened -

worse luck - to folk sayin', "What would ye do with a lame oul' woman?"

but I had learned my lesson; the Flanagan girls gave me the scunner

(disgust); so, as I said, I sat down beside Susy. Susy was a niece of

the Teggarty's, an' she owned thirty acres of lan', not to speak of bog

land, so she was no pauper. "It's a warm evenin', Susy," sis I.

"It's all in the way you take things," sis she. "What d'ye mane?"

sis I. Her nixt question took me unawares. "What forder

(progress) did ye make with the Flanagan girls?" "The Flanagan girls,"

sis I; "sure they're only 'bletherskites'; they ought to go from home

to some place where nobody knows them, to show off." "All the same,"

sis she, "you were took on with them." "Oh, for that matter,"

sis I, "a body has to pass himself; they're good sport - London

born ye know." Susy laughed. Jist then the Teggarty's called out

that the tay was ready. I wanted no tay; so whilst the others was

movin' into Teggarty's parlour I stole out by m'self. The moon was in

the full, an' the stars was shinin' in the heavens. I'm no scholar,

but I learn a lot from nature: when I'm all "me lone" I can sense things as

I look up at God's great firmament. At these times there comes a peace

to my heart and noble resolves. As I stood there I thought of Susy.

Susy, like m'self, was fond of nature; she was always cheery an'

bright, no put on - jist natural, an' I always knowed she had it in her to

make a man happy. But what the people would say kept me back all these

years, an' there the thing lay. The Flanagans turned the scale for me;

I seen things as nivir before, an' so under God's beautiful sky I made the

resolve that I would marry Susy. When the party broke up I helped Susy

on with her jacket, an' saw her safely home. As we went along I says

to her, "How is the crops lookin', Susy?" "Not so bad,"

sis she, "considerin'." "Considerin' what?" sis I. "Och

well, ye know, Paddy, I have no man to look after the workers." "How

would ye like me to do that, Susy?" Now I needn't set down any more,

other than to say that I got the job. I nivir rued it - no, nivir.

Sometimes when I'm a bit crusty with Susy (an' min' ye I have no reason to

be so), she looks over her spectacles at me an' says, "Paddy, ye

should have married one of the Flanagan girls." Then I jist turn away

to hide a smile.

Old-Time Memories

Sitting by the fire

to-night musing on the past, the thought came to my mind that I would pass

on a few memories of my early days. I was blowing up the embers at the

time. Being an old-fashioned woman I use bellows, and many a time I

lean my elbows on the same bellows and gaze into the glowing coals, for

often scenes of the past are pictured there. I don't know how these

things happen, but one face comes up again and again, and then fades away;

others anon take its place - forms, shadowy forms of those whom "I

have loved long since and lost awhile." Memory is my only company, for

I live alone. Some people dread a lonely life, but I find mine

anything but dull, living as I do in the past. It may be my

old-fashioned notion, but times are not as they were when I was young.

Less friendliness exists now, more "hurry-scurry" and this

"time-saving" craze. Long ago, folk visited one another in a

leisurely way. There was no "ringing-up" your friend.

when I look at all the innovations - breakfast on the train, electric light,

motors, and flying machines - I feel glad that the most part of my life is

over. However, it was not about modern improvements I meant to write,

for I am an unlearned woman, old and full of years, but merely to set forth

some memories of "days that are gone." I am the only one left of the

generation I write about, and I feel I am treading on sacred ground.

Someone has written, "To-day is commonplace, yesterday is glorified by

memory."

Memory beings me back to the little village of Purdysburn, within three

miles of Belfast, in which was my home. I think I can see that old

homestead as it was in those far-off days - a dear, roomy house with lofty

windows, over which hung festoons of roses, rambler roses, which drooped

down to caress the honeysuckle that clambered up over the spacious porch.

But it is the memory of the garden that holds for me the greatest charm.

I wish I could describe it as it was in the days of my youth, with its dear

old-fashioned flowers. Flowers of to-day may excel them in variety of

blooms, but old-time flowers are to me like old friends, old songs - because

they abide with us for ever. In memory's garden I see the tall

foxgloves, the stately bluebell, the ever-charming hollyhocks that grew

around the old sun-dial, the neat boxwood border that enclosed the lilies,

sweet-Jane, winter cherries, and other old-time flowers. Again I fancy

I can see the syringa arbour where, as children, we played and dreamy dreams

in the long summer days. As the years passed on we had other "ploys"

there - family conclaves, courtships, merry-makings. As I think of it

all I wipe away a tear, for, alack-a-day! all my early friends who

figured there are now lying in the valley, asleep, and the summer-house is

no more. The recollection of it all lingers with me still, like the

last rays of the setting sun which glorifies all around - the memory of that

home garden fills my heart, One corner was reserved for the bees that

from

Old-fashioned flowers their honey did make

In the old-fashioned way, in their houses of straw,

Contented and happy, for fashion's no law

To the bee.

Honey was more used then

than at present (strange). Mother had a custom of telling the bees all

her troubles. Once she neglected doing so, and they left and never

returned. Some of our neighbours who kept hives had a similar

experience. It was a popular belief then, and I have since heard of

English beekeepers who were most particular about telling the bees of the

death or other trouble in their family. We had a great collection of

herbs in our garden that "cured every ill." Doctors nowadays

smile at the name of these simple remedies, because they are considered

"out-of-date." Yet I believe with these same herbs mother cured more

people than the doctor. There was simplicity of living in those days.

Newspapers were scarce. Our paper was passed round to half a dozen

people. Very often the neighbours gathered round our hearth in the

evenings to hear the News-Letter and Commercial Chronicle read, and to talk

over the politics of that time. Those were the days of Palmerston and

Peel. Nor has we many magazines: The Dublin Penny Journal was widely

read, Reynolds' Miscellany and The Spectator were very popular. One

other Belfast magazine called the Quizzing Glass was greatly sought after,

for in it were reflected the doings and undoings of Society. Certainly

things moved more slowly. I recollect, when a child of seven, going

with my father to see some relations off to America. I was dressed in

a little nankeen spencer, white sun-bonnet cased with flax, and a white

dimity dress. The quays at that time were well up into High Street.

The vessel that our friends sailed in was very different from those of

to-day. I remember quite well seeing the bunks, which looked to my

youthful eyes very dark and uncomfortable. The voyage to New York

occupied sixteen weeks - that was eighty years ago. (1858)

Father predicted then that there would come a time when the journey would be

accomplished in sixteen days, little dreaming that I should live to see it

done in six days, or even less than six.

My father was

"everybody's body"; by that saying I mean he was a public man.

He held a government situation, and acted as tutor to gentlemen's sons in

the neighbourhood. He was a surveyor of land as well. In those

days few of the peasant class could write, and often of an evening father

was called upon by someone who wanted him to act as scribe. I remember

hearing one address him after this fashion: "Mr. Grey, I want ye to

write to our Tammy in Ameriky an' say to him we hope he's well, an' that we

are all well, an' that we hope he's gettin' on well." Often father

would lay down his quill, unable to proceed, it being so laughable,

Then the visitor proceeded: "An' Mr. Grey, tell Tammy that tho' we're

poorer than iver, if he doesn't like over beyont, tell him to come home to

his mother an' me, an' we'll share our last pratie with him, we will, God

bless him!" It wasn't every day the working class could afford to send

letters to America, as the postage of a letter to New York at that time cost

one shilling. Labourers' wages were 6s. per week, and out of that sum

1s. went for rent. I have known large families reared on 5s. per week.

Certainly, they grew their own potatoes, which with milk formed their

principal article of diet. Tea was 5s. per pound: that beverage only

appeared on their tables on Sundays. Sugar was one shilling per pound,

butcher's meat four-pence per pound, and eggs fourpence per dozen.

White bread, as baker's loaf was then called, was considered a luxury, and

was bought on great occasions only, such as weddings and christenings.

I remember in my early days going to Ogden's in High Street for pastry of a

kind that's not to be had nowadays, and to Linden's, Corn Market, for wine

biscuits and spice cakes. It would be difficult for the present

generation to imagine what Belfast was like eighty years ago. Few of

the young folk now could say where Montgomery's Market (now Castle Market)

is situated, yet I remember farmers selling their produce there. Those

were the days of the stage coaches. It seems to me but yesterday that

the mail coach with its four fine horses started from the "Donegall Arms" in

Castle Place for Dublin. Crowds would assemble when the coaches were

expected back, to hear the latest news from the metropolis. The

coaches now belong to the past, and with them has gone the kindly sentiment

of that time. Gone likewise are the old familiar faces, and strangers

and stranger ways now occupy the public arena.

One eventful day stands

out clearly through the mist of the years - the day that saw the first train

leave Belfast on its way to Lisburn. The excitement that event caused

is past the telling. Farm hands left their work in the fields, women

threw aside their spinning-wheels, and all made for the nearest point of

vantage. My mother and I viewed it from Pow's Hill. As a matter

of fact we saw only the funnel and the smoke; all the same, that was a

red-letter day. I can well remember the thrill of wonderment that

possessed me as I looked after "the iron horse," as the engine was

called. Some said it was uncanny, others that the devil had something

to do with the wonderful monster. Certainly the noise the engine made

and the clitter-clatter of the metals were to our ears very frightsome.

How many are living now, I wonder, who saw that train! Some time

afterwards we went for a jaunt to Lisburn in it. It was a rainy day,

and as there was no covering overhead we had to keep our umbrellas up; in

fact, the carriages were made somewhat after the pattern of the cattle

waggons of to-day. I remember being greatly amused watching the drips

off a lady's umbrella trickle down a man's back - inside his collar - and

the man in question took it so patiently, I verily believe he thought this

infliction part of the train arrangement. I also remember hearing my

father say that when the gentry travelled to Dublin in the early part of the

last century they always made their wills before starting. They drove

to the metropolis in their own carriages drawn by four horses with

postillions. Most old people like to think back to their childhood's

days - to the days of "make-believe." I often say that the children of

this generation have more advantages than we had. Our toys were few;

certainly we had dolls, but of a kind that would be thought ugly now - stick

dolls with terrible faces. Nor had we many juvenile books. The

Children of the Abbey was widely read; and later, Carleton, Lever, and Miss

Porter's works. Youngsters nowadays are satiated with literature and

throw away what we would have prized and treasured. Making samplers

occupied our spare time - every girl made a sampler in cross-stitch, which

contained the alphabet, usually with a verse underneath and the worker's

name. They were very frequently framed - I believe, indeed, our

parlour boasted of four such samplers. Quite lately, I came across the

remains of one I made when I was ten years of age; it is old now and faded -

only the name is legible: "Jane Grey. Anno Domini, 1835."

Children then were taught to know the value of time, and to have a time for

everything. Sewing, knitting, and spinning were our chief

accomplishments - sewing machine were unknown. In after years, Sandy

Robinson, the tailor, bought one, and the people far and near flocked to see

it, and so surprised were they to see how quickly the wonderful machine

could sew that Sandy was called "the steam tailor" ever after.

The spinning-wheel, now finds a place in lofts and storerooms, and reels are

hung up in solitary state on kitchen walls. One hears no more the

pleasant "birr" of the dear old wheel, nor the click-click of the faithful

winder. Looking through old-time papers lately, I came across the

following lines:-

------ continued below

The Auld Wife's Farewell to Her Spinning-Wheel.

"Now fare ye well my canty old wheel,

In age and youth my staff and my stay,

How gladly at gloamin' my kind auld chile,

Has watched thee busy and birrin' away.

And though we never had muckle o' gear,

And though we never were blest wi' a bairn,

For cauld and hunger we hadna' to fear

As I sung my song and I spun my yarn.

And now my poke and my staff I maun take

And wander away, an amous, to beg,

For a plack in the day is the most I can make

Though I work at my wheel till I'm blind as a cleg,

An' work till the witchin' hours of the night -

A time rather late for a thing like me.

But the gude auld days are gone out o' sight,

An' it makes the salt tear often fall from my een,

For the lords o' the mill and machine hae decreed

That buddies like me maun beg their breid."

From a very early date I

was on the habit of going twice yearly to my grandfather's house in the

Ards. My grandmother taught me to spin when I was nine years of age.

I fancy I can see her yet in her large mutch and white kerchief folded

across her breast, showing me how to handle the distaff and putting my tiny

fingers over the yarn. She was seventy years of age at that time, and

was born in 1766. Very often the late Lord Dufferin, then a youth,

when out shooting, would call on his way home to see grandmother; she always

handed him her snuff-box on these occasions, and he, laughingly, would tap

the lid and take a pinch. They then would crack jokes together.

He was very chatty - many an hour he spent in that old farm-house.

Nothing pleased my childish imagination better than to hear my grandfather

on a winter's night, when we would all be seated around the peat fire,

relate how at the time of the rising in '98 he fought at the battle of

Ballynahinch. After relating the blood-curdling events of the time, he

would recite the opening verse of an old ballad, namely :-

"Did you hear of the battle of Ballynahinch,

Where the country assembled on their own defince?

They assembled together, and on they did go,

Led on by two heroes - Clokey and Munroe."

So excited would he become that he would jump up from his chair and walk

about, overcome with the emotion of the moment. Grandmother, sitting

knitting in the inglenook, would nod her head and say, "Yes, Willie,

you were aye to the front; no coward were you, my man." This allusion

was directed against my paternal grandfather, who hid in a straw stack for

fear of the red-coats - a fact that he was reminded of till the day of his

death. My mother's father was a handsome man, and stood six feet high.

He wore a bottle-green coat with skirts at the back, velveteen knee

breeches, and fawn gaiters with moth-o'-pearl buttons. He had large

buckles on his shoes, and his hat was of a curious cut, not unlike the shape

of a crock turned upside down; such was the style or fashion of that day.

I happened to be on a visit there at the time of the great storm of '39.

There have been many severe storms since, but all put together would be a

mere bagatelle compared with that awful hurricane. It seemed for the

time as if the elements were let loose; so unearthly was the wild shrieking

sound of the wind that it is past my power to describe. Many thought

the last day had come. Windows were blown in, doors taken off their

hinges and carried, or should I say hurled, away for miles. I remember

all in the house stood with their backs to the door as a precaution to

prevent it from being blown in. During a lull in the gale my uncle

ventured out to see to the cattle. Looking through a window by the

light of the moon, I saw him carried right off his feet and dashed against a

stone wall about twenty yards away. A stack of corn just then was

carried away clean off the stone pillars and deposited intact at the extreme

end of the haggard, as if it had been built there. This was considered

a most wonderful phenomenon. The thatch was blown off hundreds of

houses, and very frequently the walls fell in. Animals without number

were lost in the merciless fury. To add to the weirdness of it all,

the two house dogs kept howling most dismally. I pray God such a storm

may never visit our shores again. Later, on returning home, I found

that nearly all the giant trees, centuries old, had been uprooted and had

turned somersault; in fact, with their branches resting on the ground and

their immense roots in mid-air. It was such a wonderful sight that the

Squire would not allow them to be removed for a long time.

Amongst my cogitations I

often think if the people I used to know, who are dead and gone, could come

to life again, and see the electric light switched on, alack-a-day, I verily

believe they would want back to their rest again. What a change from

the days of the tallow candle! The candle was the only artificial

light to be had in country places at that time. They were placed in

large candlesticks which stood on the floor and could be adjusted to any

height by pressing a spring. I remember my little brothers used to

amuse themselves shooting the candle up to the ceiling, which was rather a

dangerous practice. Somehow, to my mind, candles showed a better light

then than they do now. Composites were used on Sundays only and when

we had company; then the great brass candlesticks were brought out as well

as the silver snuffers. I remember hearing at the time of the American

War between the Northern and Southern States of a woman who went to buy

candles. The shopkeeper remarked that candles were dearer now as

tallow was up in price owing to the American War. "The Ameriky War,"

she replied; "bad luck to them, and do they fight with candle light?"

Writing of candles beings up an incident to my mind. Dr. Hunter and my

father were in the habit of having a game of cards occasionally at our home.

On one particular night - it was the small hours of the morning in fact, and

all the household had long since retired to rest - they were playing an

interesting game, when suddenly the candle burnt out. The fire had

burnt out too, and matches then were unknown. In the search for

candles, both played blind man's buff, and, in trying to make as little

noise as possible, made all the more - plates rattled off the dresser, but

still the search went on. There were high stakes on the game, and

light must be procured at any price. At length my father stumbled on a

heather broom, which was promptly tied to the candlestick, and with the aid

of the tinder box, which every man in those days carried in his pocket, the

besom was set alight, and while it burned my father won the game.

"Burning the besom" became a proverb in our house ever after.

I wonder if any of the

present generation have ever been to a "quilting"? In the time of full

moon there would usually be quilting parties all over the country. I

remember, when a girl of fifteen, going in charge of our servant, Patience

Lalor, to a "quilting" at a farm-house convenient to Shaw's Bridge. At

these functions the girls would assemble early in the afternoon and commence

sewing on quilts, which was called "quilting." These quilts would be

spread out on trestles or frames - I have seen as many as six young women

sit sewing around one of these frames. After the quilting process was

over, and the frames cleared away, tea would be served. Then "the

boys" dropped in at "day-li'-gone" and a fiddler would strike up a stirring

tune - the girls retiring to one end of the barn and the boys to the other.

Then came the choosing of partners: two chairs were placed in the centre of

the floor, and to one of these seats a "gallant" would bring the girl he

liked best. A song was then sung which was called the "Marrying Song,"

and when all the lads and lasses got "married" after this fashion, the fun

began. That was a memorable night for Patience Lalor. Poor

Patience! I see her in fancy yet dancing a jig with her sweetheart,

Bob Gillespie. Bob was a ploughman; all the same he was a very nimble

dancer. To my mind there is nothing half so uplifting as an Irish jig

or reel, and only an Irishman can put the "go" or "dash" into it.

Patience was in high glee that evening. She was a bonnie lass, with

cheeks like roses and flashing eyes; very witty was she, and had her answer

ready for all comers. As I have already said, she was our

maid-of-all-work. She came to live with us when she was twelve years

of age, and stayed until she got married twenty years later. Servants

in those days did not change their situations as now; your servant was your

friend then. That, indeed, was a memorable quilting night for

Patience, for Bob popped the question, and a few weeks later the marriage

took place. It seems like yesterday that I saw Patience on her wedding

morn attired in a slate-coloured bombazine dress set off with pink ribbons,

her hair done up in curls that clustered over her ears, and finished off at

the back by a high comb. Weddings in those days were very different

from what one is accustomed to see now. Marriage presents were unheard

of; now, present-giving is the rage; it has become a "fever" in

fact, and I like it not.

The year following the

exit of Patience from our home (1848) saw a great shadow fall over our land.

It was called the year of the "blight"; that is, total failure of the

potato crop. The blight extended well through the year '49.

Those were dark days for Ireland; the suffering caused by want, then, has

never been told, for there were many who hid their extreme poverty and so

died of slow starvation. As I have previously stated, the peasant

class dieted mostly on potatoes; in other words, potatoes were the only

article of food obtainable for breakfast, dinner, and tea. The best

potatoes in my young days were called black seedlings, and sold at 1s. 6d.

per cwt. Indian meal was introduced into the country then; somehow the

peasantry disliked it so much that they nicknamed if "sawdust."

Alack-a-day! the misery of that time is untellable. One incident comes

to my mind as I write. Jimmy Duff, the village shoemaker, together

with his apprentices, dug over half an acre of ground one day in order to

obtain a meal of potatoes. They succeeded in getting a small

basketful. Just at that moment the hounds and red-coats bounded over a

hedge close by; each digger threw down his spade, and made off after the

chase. My sister, who happened to be on a neighbouring hill watching

the sport, seized her opportunity and ran off to the potato field, and

carried away the basket of "spuds." No one knew of their destination

save the Widow Maguire, to whom my sister gave them, nor could anyone

imagine the chagrin of the diggers when they returned from the hunt to find

their booty gone - the outcome of a day's labour. There are few living

now who remember those terrible years.

These old-time memories are ever with me; the quiet and east-going pace

lived by us all in

those far-off years is in strange contrast with the bustle of to-day, and

the recollection

of it all brings peace to my heart. So as I sit by my hearth to-night,

I poke up the

embers and see all these scenes reflected there, till they disappear. as I

shall

soon, when the day is over.

Louise McKay

+ + + + + + + + + +

Click here for a more complete account

of this volume and the lists of soldiers and memorials

Northern Banking Co. Limited, Belfast

1824 Centenary Volume 1924

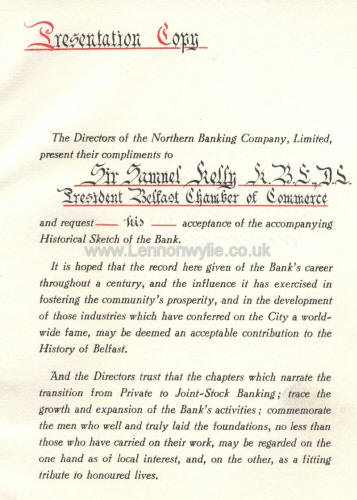

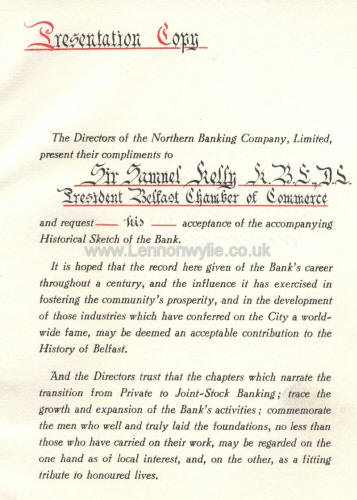

Presentation Copy

The Directors of the Northern Banking Company, Limited, present their

compliments to

Sir Samuel Kelly, K.B.E., D.S.

President Belfast Chamber of Commerce

and request his acceptance of the accompanying Historical Sketch of the

Book.

It is hoped that the record here given of the Bank's career throughout a

century, and the influence it has exercised in fostering the community's

prosperity, and in the development of those industries which have conferred

on the City a world-wide fame, may be deemed an acceptable contribution to

the History of Belfast.

And the Directors trust that the chapters which narrate the transition from

Private to Joint-Stock Banking; trace the growth and expansion of the Bank's

activities; commemorate the men who well and truly laid the foundations, no

less than those who have carried on their work, may be regarded on the one

hand as of local interest, and, on the other, as a fitting tribute to

honoured lives.

+ + + + + + + + + +

Belfast High School Magazine

December 1952 Vol. 9 No. 2

Editorial: We regret to report the death of

Rev. John S. Pyper, D.D., Senior Minister of Portrush Presbyterian Church.

Dr. Pyper was a Governor of the School from 1929-1947 and a brother of Mr.

H. S. R. Pyper, B.A., a former Headmaster. We extend our deepest sympathy to

Mrs. Pyper and the family. We congratulate Mr. Abernethy on his

appointment as Head of the Science Department. We welcome must (most)

cordially our new members of Staff. Mr. Rowland-Jones is Head of the Music

Department in succession to Mr. Orton. Mr. Ferris has added to the strength

of our Science Department. Miss McConnell, Miss Smyth and Miss Shearer have

been appointed to posts in Ardilea House. Miss Helen Rea has taken Miss

Robinson's place at Jordanstown. We giver a very special welcome to Miss

Kirkwood, not so long ago one of our own pupils, who has now completed a

distinguished degree course in Mathematics at Queen's University, and has

returned to us as a member of the High School Staff. We also welcome two new

part-time teachers - Rev. R. H. Kimber has taken over the major share of the

teaching of Scripture to our Senior forms. Miss Whitsitt is responsible for

the teaching of Art in Ardilea House. We give a warm Ulster welcome to

M. Gauduchon and hope he will enjoy this year at the High School.

Congratulations to Mr. and Mrs. Heaney on the occasi0on of their marriage.

They have our very best wishes for their future happiness. Congratulations

to Mr. and Mrs. Wood on the birth of a daughter. We send congratulations to

Mr. and Mrs. J. Craig on the birth of a son. Mrs. Craig is a Vice-President

of the Old Girls' Association and a former Head of the Mathematics

Department. Congratulations to Miss Loughrin on her marriage to Mr. John A.

Phillips. We send them our very best wishes. We congratulate Miss E. G.

Henderson, N.F.F., on being awarded her L.G.S.M., A.T.C.L., A.L.C.M. and

L.A.M. (with Gold Medal). many many more

names mentioned throughout this magazine CLICK on images to enlarge.

Cricket 1st XI 1952

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE

Tennis 1952

Crossword Answers

+ + + + + + + + + +

Laurel and Gold Anthology,

John R. Crossland - John E. Donaghey, Coolnafranky House, Cookstown

Little Trotty Wagtail: Little trotty wagtail, he went in the rain,

and twittering, tottering sideways he ne'er got straight again. He stooped

to get a worm, and looked up to get a fly, and then he flew away ere his

feathers they were dry. Little trotty wagtail, he waddled in the

mud, And left his little footmarks, trample where he would, he waddled in

the water-pudge, and waggle went his tail; and chirrupt up his wings to dry

upon the garden rail. Little trotty wagtail, you nimble all

about, and in the dimpling water-pudge you waddle in and out; your home is

high at hand, and in the warm pig-sty, so, little Master Wagtail, I'll bid

you a good-bye. John Clare

The Owl: When cats run home and light is come, and dew is cold upon

the ground, and the far-off stream is dumb, and the whirring sail goes

round, and the whirring sail goes round, alone and warming his five wits,

the white owl in the belfry sits. When merry milkmaids click the

latch, and rarely smells the new mown hay, and the cock hath sung beneath

the thatch, Twice or thrice his roundelay, twice or thrice his roundelay,

alone and warming his five wits, the white owl in the belfry sits. Alfred

Lord Tennyson

The White Sea-Gull: The white seagull, the wild seagull! a joyful

bird is he, as he lies like a cradled thing at rest, in the arms of a sunny

sea! the little waves wash to and fro, and the white gull lies asleep; as

the fisher's boat, with breeze and tide, goes merrily over the deep, the

ship, with her fair sails set, goes by, and her people stand no more.

How the seagull sits on the rocking waves, as still as an anchored boat, the

sea id fresh, and the sea is fair, and the sky calm overhead; and the

seagull lies on the deep, deep sea, like a king in his royal bed! Mary

Howitt

click images to read more

The Touch of the Master's Hand

+ + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + +

+ + + + + + + + + +

|