|

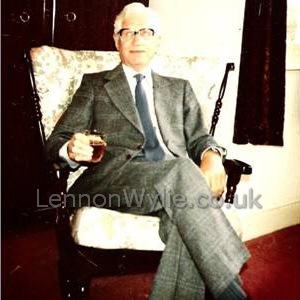

Memoirs of Thomas Herbert Coulter.

December 2009

As I am now in my

ninety-third year, my family have asked me to write an account of my

eventful life.

I

was born August 1916 in a small village called Dunkineely, County

Donegal, the fifth child born to my parents, Thomas and Annie Coulter

(nee Christie), who went on to have four more children. My father was

one of twelve children, born in a thatched cottage near Dunkineely. His

father had a small farm. I

was born August 1916 in a small village called Dunkineely, County

Donegal, the fifth child born to my parents, Thomas and Annie Coulter

(nee Christie), who went on to have four more children. My father was

one of twelve children, born in a thatched cottage near Dunkineely. His

father had a small farm.

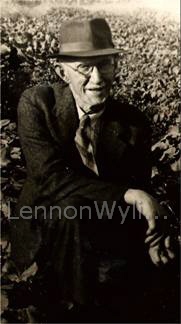

My

father left school at the age of fourteen and later went to Londonderry

to 'serve his time' in the drapery business. He then returned to

Dunkineely and set up business with his brother Matt. Whilst Matt

continued in the grocery business, my father started a drapery shop on

the other side of the street. My father was what would nowadays be

called 'an entrepreneur par excellence', selling not only clothes and

shoes, but radios, bicycles, as well as having a petrol pump on the

pavement.

He

was also the local undertaker, providing coffins and shrouds. Another of

his activities was helping local people who wished to emigrate to

America. He dealt with the necessary paperwork and took their

photographs for passports, using a Brownie box camera. He

was also the local undertaker, providing coffins and shrouds. Another of

his activities was helping local people who wished to emigrate to

America. He dealt with the necessary paperwork and took their

photographs for passports, using a Brownie box camera.

At the time I was born my father must have been very worried about three

of his brothers who had emigrated to Canada. When the war broke out they

joined the Canadian Army and served in France. They all survived the war

and returned to Canada, but subsequently one of them returned to

Donegal, where he died as a result of his war wounds.

Not long after the war ended (in 1918) the IRA resumed their campaign to

drive the British out of Ireland. They were quite active in County

Donegal, and as my father was Protestant and of Scottish descent, he was

one of their targets. I remember them raiding his shop on a few

occasions, threatening him, and once made an attempt to burn down the

front door. There were not many cars in the district at that time, and

the IRA forced him to take his car out during the night and drive them

to meetings outside the village. I believe that when the Free State

Government later took control they paid him some compensation for the

losses he had suffered.

Like

all my family, I started my education at three years of age at

Killaghtee National School, which was under the management of the local

rector. There were two lady teachers and the Headmaster, Master

Gillespie. Whilst the ladies were good teachers and very kind to us, I

would say he was a sadist who frequently beat the children. Fortunately

I myself escaped this, but I remember that my brother Arthur was beaten

by him on his first day at school because he had been cheeky. I consider

that at this school I received a good start to my education. My family

always went to church twice on Sundays and also attended Sunday School

before the morning service. Like

all my family, I started my education at three years of age at

Killaghtee National School, which was under the management of the local

rector. There were two lady teachers and the Headmaster, Master

Gillespie. Whilst the ladies were good teachers and very kind to us, I

would say he was a sadist who frequently beat the children. Fortunately

I myself escaped this, but I remember that my brother Arthur was beaten

by him on his first day at school because he had been cheeky. I consider

that at this school I received a good start to my education. My family

always went to church twice on Sundays and also attended Sunday School

before the morning service.

When

things returned to normal after the Free State Government took control,

life for us was very pleasant, especially in the summer when I remember

many happy days bathing in the sea, about half a mile away from the

village. I also played football with the local boys; many of them, of

course, were Catholics but we all got on well together. The highlight of

the year was the Sunday School excursion by train to Rossnowlagh, when

we had picnics and games on the beach, which we enjoyed very

much. When

things returned to normal after the Free State Government took control,

life for us was very pleasant, especially in the summer when I remember

many happy days bathing in the sea, about half a mile away from the

village. I also played football with the local boys; many of them, of

course, were Catholics but we all got on well together. The highlight of

the year was the Sunday School excursion by train to Rossnowlagh, when

we had picnics and games on the beach, which we enjoyed very

much.

There

was no electricity or gas in Dunkineely, but my father installed a gas

generator to provide lighting for the shop and the house. There were two

pumps in the village from which we obtained our water supply. We had to

walk to a farm some distance away to buy milk, which we carried home in

tin cans, and also bought buttermilk which we all liked very much.

I

remember one of the great excitements of my childhood was when the local

doctor, who lived next door to the school, invited some of us into his

house to listen to the radio for the first time. We were thrilled to

hear Big Ben from London, and also listened to the commentary on the

Boat Race. The rector was also kind to the children and used to take us

out in his sailing boat round the bay at Bruckless and gave us picnics

on the shore. The last few years of my schooling at Killaghtee were

enjoyable and I made good progress. I

remember one of the great excitements of my childhood was when the local

doctor, who lived next door to the school, invited some of us into his

house to listen to the radio for the first time. We were thrilled to

hear Big Ben from London, and also listened to the commentary on the

Boat Race. The rector was also kind to the children and used to take us

out in his sailing boat round the bay at Bruckless and gave us picnics

on the shore. The last few years of my schooling at Killaghtee were

enjoyable and I made good progress.

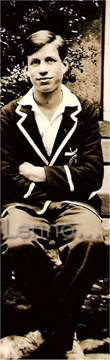

When

I was twelve years old I sat an examination organised by the Church of

Ireland for a place as a boarder at Sligo Grammar School. I acquitted

myself well, being placed first in Ireland, and was awarded a Foundation

Scholarship, which meant that my father had to pay only £15 per annum

instead of the full fee of £60. Sligo was forty miles from Dunkineely,

so I could only go home at holiday times. When I started at the Grammar

School in 1929 my two older brothers, Bob and Norman, were also there,

and I was therefore known as 'Coulter 3'. I adapted well to my new life

and enjoyed studying new subjects, especially Latin and French, which I

still enjoy to this day. At the time I did not realise how fortunate I

was to be in small classes (sometimes only 15), so that we received

almost individual attention, from excellent teachers. Every evening from

6.30, for about three hours, we had a session known as "Prep.

", when we studied and prepared our work for the next day under the

supervision of a master.

I

greatly enjoyed all the sports at the school, rugby, cricket, tennis and

badminton, and during my last two years I played on the school teams. We

played against a number of schools, such as Portora, Mount joy and

Ranelagh. Every Sunday we went twice to church, walking in

"crocodile" to Calry Church. The girls from the High School

also attended-- and I am afraid their presence somewhat distracted our

attention from the service. We were, however, never allowed to mix with

them, either at church or at any other social activities. I was a member

of an active Scout Group and the highlight of the year was our annual

camp on the shores of Lough Gill (not far from the Isle of Innisfree).

After four years at Sligo, I sat the Intermediate Examination organised

by the Government and was awarded a scholarship to Mountjoy School,

Dublin

This

school was very different from Sligo Grammar School. It was housed in a

number of old terrace houses, overlooking Mountjoy Square, which was

situated less than a mile from the centre of Dublin. We did Physical

Training under the supervision of a former Army Sergeant Major in the

large yard at the back of the building - rather grim, as I remember. We

had to walk some distance to our playing fields at Clontarf, past the

famous Croke Park, where only Gaelic games were played. I played in the

Senior Cup teams both in rugby and cricket and we played against many of

the well-known schools in Dublin.

The standard of education was very high and, yet again, the classes

never consisted of more than 15 to 20 pupils. I enjoyed studying most of

the subjects taught, especially Latin, French, Irish and even Greek for

a year. However, we had a reputedly brilliant Maths teacher who taught

us Higher Maths such as the Binomial Theorem, Calculus, and Co-ordinate

Geometry, all of which were "Greek" to me! I had been quite

good at elementary maths, but not the higher levels.

The Headmaster, Rev. William Anderson, was a very nice old man with a

flowing white beard. He was also reputed to be a brilliant maths teacher

but he didn't have the pleasure of enlightening me in this subject, -

lucky for both of us!

There was a large and grim basement in the buildings, where some of the

boys used to retire to have a secret smoke. I am sure the teachers knew

what was going on down there but they did not interfere.

As my father's business was not doing very well in the thirties, I had

to manage with very little pocket money and so could not afford to

sample many of the delights on offer in the city of Dublin. There was so

much to see in a very historic city.

We paraded twice on Sundays to St. George' s Church near Mount joy and I

must confess I had so much of church attendance at school that when I

started work in Belfast I seldom attended church, and this pattern

lasted until the end of the war in 1945.

When I was eighteen I sat the Northern Ireland Civil Service Clerkship

exam in December 1934 and was called for an interview at Stormont early

in 1935. I was interviewed by half a dozen very important-looking

gentlemen who treated me very kindly. They were very interested to hear

that I was quite a good rugby player and would be likely to join the

Civil Service Rugby Club, which I did.

Soon after that I was informed that I had been successful in gaining a

place on the staff of the Ministry of Education at Stormont. Our Mount

joy Senior Cup rugby team had won a few rounds in the competition and on

my last day at Mount joy I played full-back for the team. The final

score was nil all and after the match I had to rush to catch the train

for Belfast in order to start work at Stormont on the following morning,

2nd March 1935. Shortly after, I was very flattered to be called up to

speak to one of the senior officers, Mr. Brownell, who was himself an

old Mountjoy boy, who told me that the headmaster had phoned to ask if I

could return for the replay. I declined the offer as I had developed a

bad cold and was not in very good form.

I first worked in the Secondary School Branch under a Mr. Bowman, who

was the Staff Officer. Later I transferred to the Technical School

Branch. After eighteen months at Stormont I moved with the Ministry to

an old building in Ormeau Avenue, which was not a very pleasant change.

During that time Europe was in turmoil as Hitler was growing in strength

and threatening nations bordering on Germany. Churchill was warning our

Government to re-arm to meet the Germans' threat, but nobody listened to

him. The country was still suffering from the horrors of the 1914/18 war

and did not dare to think of re-arming to meet the increasing power of

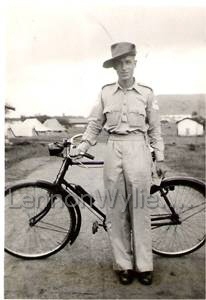

Germany. And so, in the Spring of 1939, when the Government finally

decided to re-arm, I, like thousands of other young men in Ulster,

volunteered for service in a Territorial Regiment, the 8th Belfast Heavy

Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, Supplementary Reserve. We were

issued with dungarees and Army boots and went to Dunmore Park, off the

Antrim Road, two or three evenings a week to train. This continued until

the month of August. In the middle of that month I went on holiday to

Donegal and Sligo and while I was there I received a call through my

parents to join the Army full-time, ten days before the war broke out.

After a few days'

training at Dunmore Park we were moved to Kinnegar Camp in Holywood on

the shores of Belfast Lough.

We were accommodated in tents and

the facilities were rather primitive. I was performing my ablutions in

the open air when I heard Neville Chamberlain's announcement on the

radio that we were at war with Germany. The general feeling at that time

was that the war would be short-lived and would be over by Christmas -

little did we know what was in front of us for the next six years!

Whilst we were at Kinnegar there was a lot of rain during September and

October, so conditions were not pleasant for us. We had some old large

guns, on which we did some training.

In late

October we moved to Bude in North Cornwall, where yet again we were

housed in tents, this time at the top of the sea-cliff. Our sojourn

there was cut short by a fierce storm which blew all our tents down in

the middle of the night. Pandemonium reigned, and this was the first

time in the war that we were issued with rum, which cheered us up a bit.

We were hurriedly transported to Bude, and were accommodated in various

places. I remember spending the next two nights sleeping under the

counter in an empty shop. After being billeted in Bude for a short time,

we moved to Deepcut Barracks, near Aldershot, a rather grim place which,

I understand, was built during the Napoleonic Wars. There we were

equipped with guns and all the necessary items for service abroad.

Just a week before Christmas we left Southampton for

Cherbourg. There we were put on a train and travelled through Normandy

to Rouen and then to Le Havre. I still remember the railway wagons with

their inscriptions - "40 Hommes, 8 Chevaux".

In Le Havre we were billeted in La Gare Maritime down at the docks, all

thousand of us. We slept on our palliasse on a hard floor. The first

peculiarly French thing we saw was a bidet, which we had never seen

before and there was great speculation as to what it was used for! I

remember the weather was bitterly cold for the next few months.

Fortunately, after a week we moved to a big house in St. Adresse, called

the Villa Maritime, and we remained there for a couple of months. We

were very comfortable there, with plenty of heat and a lovely view of

the sea. Of course, the "real" war did not start until the

Germans invaded Belgium and France in May 1940, so until then life was

very pleasant for us. As I had learned French at school for six years, I

was one of the few soldiers who were able to communicate with the French

people, and it was during this time that I entered into conversation

with a young French girl. I remember my opening gambit was "Aimez-vous

la societe des soldats Britannique?"

which amused her very much, as I should have used the word "compagnie".

She spoke no English at all, so I had to carry on a conversation as best

I could in my schoolbook French. Her name was Genevieve and we agreed to

meet on the following Sunday at the Hotel de Ville.

When the day arrived I spruced myself up and hastened to the rendezvous

with great anticipation. Imagine my disappointment when she arrived and

I saw that she was accompanied by her little brother. He had been sent,

I presume by their mother, to act as a chaperon! However, we went to the

cinema and continued to do so every Sunday for some time. I was invited

to their house for dinner on a number of occasions and got on very well

with their mother, who was very kind to me.

Our next move was across the River Seine to a campsite outside the

lovely old town of Honfleur. I remained in Le Havre, billeted with the

RASC, as I had the task of collecting the rations from a big depot in Le

Havre and taking them by the ferry across the Seine to our Battery near

Honfleur every day. This journey by ferry took more than two hours,

whereas today, with the new bridge near Le Havre, the journey takes

about half an hour.

When the German invasion began on 10 May 1940 our regiment moved further

north. The 21st Battery moved still further north and unfortunately

ended up at Dunkirk. Fortunately, however, most of them were able to

escape to England. As the Germans advanced our Battery retreated, with

our big guns, to south of the River Seine near Rouen. (I should explain

that there were three Batteries in an Artillery Regiment. ) There our

guns were established while the German tanks massed on the north side of

the river. Our guns fired on their tanks, but the Germans sent up a

spotter plane, pin-pointed our gun positions and fired a large number of

shells which damaged some of our guns and caused a number of casualties.

As the situation was becoming hopeless, we got the order to withdraw

and, before doing so, the guns had to be put out of action so that they

would not be of any use to the Germans. We were fortunate in having

lorries to transport us southwards. The journey at times was very

troublesome as we had to make our way on roads filled with French

refugees who were fleeing from the Germans.

We did feel some guilt at abandoning them to the mercy of the Huns, but

the latter had prepared thoroughly for war, whereas our efforts up to

that point were pitiful in comparison.

Finally, after a few days, we arrived in St Malo in Brittany on

9th June, long after the evacuation at Dunkirk. Our other Battery, the

22nd, escaped from Cherbourg. In St. Malo we lay in the open on the

race-course for a week before the Army authorities found an old boat to

take us to Plymouth. They packed as many as possible on to the boat, so

the voyage was not very comfortable, but uneventful. Also, during our

stay in St. Malo we were sitting targets for the Luftwaffe, but they

left us alone. However, two hundred miles south at St. Nazaire they

attacked the troopship Lancastria, causing thousands of casualties.

On arrival at Plymouth a train took us to Cardiff, where we had

breakfast in the Castle. The train then took us on to Pembroke, but

almost immediately turned around and our next stop was Blackpool! We

were put up in boarding houses for a few days and then transferred to

one of the holiday camps. At that time Blackpool was full of RAF

personnel. After a few weeks in Blackpool we were transferred to

Coventry, - where my brother Bob lived. There our regiment manned a

number of gun-sites around the city until early September. During our

stay the city was bombed a few times but nothing like the terrible raid

in November, when the city was devastated. I was billeted in Meriden, a

few miles outside Coventry, on the way to Birmingham. While there I was

able to see my brother Bob quite often.

Our stay in Coventry came to an end early in September when we were

moved to London which at that time was being heavily bombed by the

Luftwaffe. Our first night in London was hectic. We were in a camp near

the Hurlingham Polo Ground and could not sleep because of guns firing

and bombs dropping. The next day we were taken to Wimbledon Common where

our guns were deployed. There we were constantly in action at night. I

cannot remember if we damaged any of the enemy planes, but I suppose we

scared them a bit. I remember the shrapnel from our burst shells could

be dangerous when it fell to earth.

We were told that the noise we made at least gave moral support to the

people living through the raids. On one occasion a land mine landed near

our site and we were very lucky to escape unhurt. We were on Wimbledon

Common all through the Battle of Britain and we saw the amazing sight of

packed formations of enemy aircraft attacking London by day and night

and the famous defence made by our RAF fighters. After the heaviest

raids we saw London burning furiously.

I shall never forget the night I was marooned in central London, and to

escape the bombing I went down into a Tube station, where the platforms

were packed with women and children, bedding down for the night and not

knowing what would meet their eyes when they got out on to the street

after the All Clear in the morning, - perhaps their homes had been

destroyed during the night.

When we were deployed on Wimbledon Common in November I remember having

to go back to Coventry to collect some vehicles. This was on the Sunday

just a few days after Coventry had been so heavily bombed by the

Luftwaffe. I was really shocked at the sight of the devastated city. As

far as I can remember, there was not an intact roof in the centre of the

city and the ruined cathedral was still smoldering. I tried to find my

brothers Bob and Arthur but without success, as they had been evacuated.

Our final posting in London was, believe it or not, in the grounds of

Wormwood Scrubs Prison. I remember so well the night of 29 December 1940

when the Germans set fire to the city of London, causing great

destruction. Standing outside the prison gates I was able to read a

newspaper by the light of the fire three or four miles away.

In January 1941 we were moved out of London up to the north-east of

England, Middlesborough, Stockton-on- Tees, Norton-on-Tees and West

Hartlepool. Fortunately, the air raids were much less frequent there.

The local people were extremely friendly and hospitable, so it was much

preferable to London. After some time in the north-east we moved to

Glasgow which had been

heavily bombed at the same time as Belfast had suffered so heavily.

There the people were also very kind to us. As we were camped out in

tents, with washing facilities at a minimum, I was very grateful one day

when a young lad, on his mother's suggestion, invited me up to his house

to have a bath and something to eat.

After a few weeks there we moved to Dundee, Aberdeen and Lossiemouth. At

that time the Germans were not attacking that part of the country, so

our only problem was the snow, which lasted for a couple of months. It

was interesting to note that Coventry was heavily raided after we left,

as was Aberdeen. After Aberdeen, as a test of our mobility, we were

ordered to travel to Hinton St George, near Crewkerne in Somerset, and

then up to Hexham in Northumberland, so I became very familiar with many

places in the UK. After all this, we were moved, all one thousand of us,

to Oldham, where we were housed in a large empty mill. I remember when I

returned from an evening out, on entering the mill, the stench of a

thousand bodies hit me in the face. I must say the people in Oldham were

very kind and friendly towards us. I should perhaps mention that the

regiment we replaced in the mill were shortly after shipped to

Singapore, where they arrived in time to be captured by the Japanese. I

suppose it could have been us!

I shall never forget the evening of 6 December 1941 in the mill, when it

was announced on the radio that Pearl Harbour had been attacked by the

Japanese and that the USA had declared

war on Japan and

Germany. We were greatly delighted, since after Dunkirk we had been

fighting the Germans all on our own, with the help, of course, of our

dominions and colonies.

Looking back on the first two years of the war, I wonder how we

survived. Of course, it was due to the bravery of our airmen and that

twenty mile strip of water separating us from the continent. The amazing

thing was that all during that period we never thought we would be

defeated.

Finally we moved to Alford, a small town near Skegness in Lincolnshire,

where we were issued with tropical kit, but our destination abroad was a

top secret. We were sent on a short embarkation leave, but I did not

think it was worthwhile going to Ireland. Shortly after, we went by

train to Gourock, on the Clyde, where we boarded the Belfast-built S.S.

Britannic, which was a large ship. Before sailing, we received a message

from Winston Churchill, saying that in the First World War the troops

had saved their country under appalling conditions of discomfort and

that we must be prepared to do the same, - not very reassuring, I can

tell you.

On board I was very fortunate as I had a comfortable berth in a cabin,

which I shared with other sergeants. The lower ranks, however had to

sleep on hammocks on the lower decks,

which could not have been very comfortable. I just cannot remember how I

passed the time during our long voyage. I must have read a lot and taken

daily exercise.

Five thousand troops embarked on this ship, which was only one of a

number of troopships, and it was amazing to see the large number of

naval ships that escorted us, presumably to protect us from German

submarines. Instead of going south, towards the north coast of Africa,

we went straight out half way to America to avoid enemy submarines based

on the west coast of France, and then turned south until we reached

Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. There we layoff for a week and,

of course, the heat was very trying. When it was a British colony it was

always referred to as the white man's grave.

An interesting ceremony took place as we crossed the equator. A member

of the crew dressed up as Neptune and took up a position beside a large

tank, which served as a swimming pool. He ordered his crew members to

'duck' anyone who had not crossed the line before. I don't know where I

was when all that took place, but I heard about it afterwards.

We then continued south, rounded the Cape, and landed at Durban on the

southeast coast of South Africa, early in July, - so we had been at sea

for over a month. We spent ten days in Durban which was a great

pleasure, after being cooped up on the ship. A large number of our lads

were Orangemen, so they made their own sashes and banners and paraded

beneath a makeshift arch around the camp, which was the famous cricket

and rugby ground where international matches are played, - Kingsmead, I

think it was called. I remember I slept on the seats of the stand. It

was most interesting that we arrived there in their mid-winter, but for

our time there, their weather was just as good as we get during our

mid-summer in Britain, - even better, with cloudless skies and warm. I

should mention that I met two middle-aged ladies who invited us to their

home and were very good to us. Unfortunately, the pubs were all closed.

A Scots regiment had been there before us and I understand had wrecked

some of them. Arriving at Durban was rather a cultural shock, as the

"whites", Indians and Africans lived separately, - Apartheid,

in effect, but I don't think it was official at that time. The Europeans

occupied the sea-front, the Indians further back, and the

"blacks" in another area. During our stay in Durban we were

taken on a trip to Zululand, not far away, and saw how they lived.

A large part of the convoy put in at Capetown and when we left Durban we

were on our own until we reached Bombay. I heard there were some

Japanese submarines in the Indian Ocean, but luckily they did not find

us. A large number of our convoy must have gone to the Middle East.

On arrival at Bombay, which was an amazing sight to us, we entrained for

a hill camp called Deolali. In the Army any person who became slightly

mad was called "Deolali tap", I suppose because if they were

not careful about protecting themselves from the sun it affected them

very much.

After

a few weeks getting acclimatised, we were put on a train for Calcutta, a

distance of a thousand miles. The train stopped for meals at a number of

stations, where we got our meals in packs and were also able to get out

and walk about. Of course, at every station we were surrounded by young

boys, shouting "Baksheesh", meaning alms. On arrival in

Calcutta, which was a very large city, the troops were billeted in

various parts of the city. There was much poverty and I remember during

the famine in 1943, on a visit back there, having to step over people

dying of hunger on the footpath. This was very disturbing. After

a few weeks getting acclimatised, we were put on a train for Calcutta, a

distance of a thousand miles. The train stopped for meals at a number of

stations, where we got our meals in packs and were also able to get out

and walk about. Of course, at every station we were surrounded by young

boys, shouting "Baksheesh", meaning alms. On arrival in

Calcutta, which was a very large city, the troops were billeted in

various parts of the city. There was much poverty and I remember during

the famine in 1943, on a visit back there, having to step over people

dying of hunger on the footpath. This was very disturbing.

While

in Calcutta I became ill with dengue fever, caused by mosquito bites,

and spent a week in a military hospital. Also in Calcutta I got a great

surprise to meet a chap who was at Sligo Grammar School with me, and we

had a very jolly evening together. He told me that he had been invalided

out of the RAF, but after a while, back in southern Ireland, he joined

up again under another name.

I should mention that thousands of the poor had no homes. They just

lived on the streets and at night they all went into the large railway

station to bed down for the night. I happened to be outside the station

early one morning and was amazed to see thousands of them coming out.

On leaving Calcutta, we made our way across the Ganges delta towards the

Burmese border. With such heavy vehicles we made very slow progress, as

the delta is broken up by many wide rivers. During that period the

regiment suffered all the problems of acclimatisation and many went down

with dysentery and malaria. We eventually reached a very good camp

consisting of bamboo huts in beautiful open country, with plane trees in

flower and very few people about, not far from Comilla. Near here we had

our first taste of being bombed by the Japanese and had a number of

casualties, including Col. James Cunningham, who was wounded but

fortunately recovered and he continued to command the regiment until the

end of the war.

At that time our armies were in full retreat before the invading

Japanese army. Thousands died when Japanese fighter planes

machine-gunned them. Disease took its toll, cholera, black water fever

and malaria and hundreds drowned crossing the rivers Irrawaddy and

Chindwin. The Japanese killed many of their prisoners by bayoneting

them. They thought our soldiers were cowards if they surrendered. Our

next stop was at the port of Chittagong, not far from the Burmese

border. There I was laid low with malaria and had to spend some time in

hospital. Just before that, our army, including the Inniskilling

Fusiliers, had moved back into the Arakan in Burma, but had been

surrounded by the Japanese and had suffered badly.

After about four months across the border in Burma, we were pulled out

and sent back to India, as very little fighting took place during the

monsoon rain. We moved back to Burma when the monsoon rains ended.

During the rainy season the roads were impassable because the surface

was just packed earth from the fields. At this stage our guns had not

many Japanese planes to fire at, as our Air Forces and the Americans had

shot many of them down. And so our guns became involved shooting at

ground targets and were very good over long ranges. One night the

Japanese came through the jungle and crept into one of our encampments

without our sentries seeing them. They blew up a number of our vehicles

before the men realised what was happening. It was not an occasion to be

proud of but fortunately there were no casualties, and replacements were

quickly forthcoming.

At this time Lord Mountbatten had arrived to take command of the South

East Asia Command. He decided that there had been too much retreating

and too little fighting it out. So instructions were issued that if the

Japanese came round behind us (which they did quite often) we were to

stay put and take them on where we were, and this was what happened at

the famous Ngakyedauk Pass battle. Part of one of our Batteries, with

some tanks, dug in and fought back.

The Japanese managed to get into the little tented field hospital and

killed everyone in it: doctors, nurses, and wounded patients in bed.

There was one general who escaped in his pyjamas. One troop was

completely surrounded and cut off for several weeks, but gallantly held

on, as instructed, with supplies being dropped to them by parachute. As

a result, one of our officers received the Military Cross and a sergeant

the Military Medal.

I shall never forget the visit Mountbatten made to our front. He got up

on a soap box and tried to raise our spirits. In his speech he said to

us: "You blighters think you are The Forgotten Army. I can tell you

they have never bloody well heard of you at home!" At that time the

troops out east were complaining that there was never much mention of

them in the newspapers at home, because all the emphasis was on the war

in Europe.

At the onslaught of the monsoon again we were pulled back to India for

some months. During that time I was given leave and made my way to

Darjeeling, about 6000 feet up the Himalayas. That was a very enjoyable

break amidst beautiful scenery. I saw in the distance the second highest

mountain in the world and could have viewed Mount Everest, had I been

prepared to get up at six o’clock in the morning. At the same time

three of our lads decided to go to Kashmir in north-west India.

Unfortunately, on their way the bus went off the road and fell 300 feet

to the bottom of a river. There were no survivors.

When we next went back into Burma the Japanese were in full retreat and

our armies advanced quickly on Rangoon. We advanced quickly down the

west coast of Burma and got as far as the islands of Akyab and Ramree.

Shortly after that I was flown back to India in an advance party to

prepare for the invasion of Malaya. I should mention that the Dakota

which took us to India looked rather fragile but, of course, it had a

great reputation for reliability.

We spent some weeks preparing for the invasion and were not too happy

about it, after over three years out east and six years' service in the

Army. However, much to our surprise, we heard the news that the

Americans had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima in Japan and another

one on Nagasaki a few days later. I considered the first bomb, dropped

on 6 August, was a great birthday present for me. Then Japan surrendered

and we were surprised and delighted to be on our way home in September

in the Stirling Castle, another ship built in Belfast. Before leaving

for home, we were told that the planned invasion of

Malaya would have been very difficult as most of the information they

had about the landing area was wrong. Actually, we would have been

landing into deep water instead of on to the gently sloping beaches we

had been told were there.

Unfortunately, the voyage home was not as comfortable as the outgoing

one, but we did not care as long as we were leaving India and Burma

behind. This time I had to sleep in a hammock on the lower decks and

there was no strong drink aboard. However, this time we did not have to

go the long haul round the Cape, as the Suez Canal was open. So we saw

the famous port of Aden, went through the Suez Canal and, of course,

passed by Gibraltar. Finally, we arrived in Liverpool but there was

no-one there to welcome us. I suppose the people had got tired welcoming

the troops home from the European theatre. Then on to

Stranraer and Larne harbour, where we were met by a band and many VIPs,

including Sir Basil Brooke, the Prime Minister. When we arrived at York

Street station we were greeted by many family and friends in great

style. I was delighted to see my mother and father there and some other

members of the family. We were all rather yellow, after having been

dosed with Mepaquin tablets for some years, and I was very thin. It was

a great feeling to be home again and to be cheered by all our families

and friends.

As far as I can remember, I went home to Donegal for most of my

fortnight's leave and so missed the welcoming victory march through the

streets of Belfast, led by their pipe bands. At the end of our leave we

returned to England and were stationed around Coventry, where I met

Phyllis, Bob's wife, for the first time. Arthur was there too after his

safe return from the Italian theatre of war. I enjoyed very much my stay

in Coventry until I was demobbed on 16 December 1945. I was issued with

civilian clothing at a depot in the west of England, before travelling

to Belfast. It was a great joy to be able to spend Christmas at home

with my parents and to feel safe at last. Of course, I did not get a

great welcome when I arrived in Dunkineely, as De Valera ensured that

Ireland remained neutral during the war, and I think he would have

preferred Germany to win.

For the last year of the war I did not feel very fit but did not suspect

there was anything wrong. I was granted demob leave until 1st April

1946, but returned to work on 1st March. During my absence on war

service I was promoted to the rank of Senior Clerk and later to Junior

Staff Officer. The Civil Service authorities thought it was only right

that officers absent on war service should not be at a disadvantage

compared with those who did not join up. When I started work on 1st

March I found it very difficult, but I must say I was treated very well

by the senior officers. After three months, I got a terrible shock when

I was promoted to the rank of Staff Officer. I had not expected such

promotion and found life rather difficult for some time. I was still a

Clerk when I left on war service, so did not really have the necessary

experience for the post. At that time the Ministry was housed in the

grounds of Stranmillis College. During the winter of 1945/46 I played a

few games of rugby, and in the summer of 1946, at my tennis club I won

the singles cup for the third time. The following summer I joined the

Civil Service Tennis Club and reached the finals of the singles. That

was the end of my tennis career as I fell ill the following year.

In

January 1947 my friend, Eddie Meyer, persuaded me to join the Masonic

Order, which I have never regretted. During that period I visited my

parents in Donegal a few times. In the autumn of that year disaster

struck when I was diagnosed as suffering from tuberculosis. I had to

stop work, but had to wait until April 1948 before I was admitted to

Forster Green Hospital in Belfast. I lay in bed there for many months

before I received a course of medicine which cured me. I was discharged

in June 1949 and returned to work, after two years' absence. I was very

fortunate to be employed in the Civil Service as I don't think any

business would have employed me in my state of health. In

January 1947 my friend, Eddie Meyer, persuaded me to join the Masonic

Order, which I have never regretted. During that period I visited my

parents in Donegal a few times. In the autumn of that year disaster

struck when I was diagnosed as suffering from tuberculosis. I had to

stop work, but had to wait until April 1948 before I was admitted to

Forster Green Hospital in Belfast. I lay in bed there for many months

before I received a course of medicine which cured me. I was discharged

in June 1949 and returned to work, after two years' absence. I was very

fortunate to be employed in the Civil Service as I don't think any

business would have employed me in my state of health.

Once again I found it difficult to get used to the office routine. I was

living with my sister, Elsie, at the time and led a quiet life. In the

summer of 1950 I went back to France to visit some of the places I had

been to at the beginning of the war. I stayed with my old girl friend,

Genevieve, and her husband in Le Havre. Five years after the end of the

war most of the town was still in ruins.

That Autumn I started attending a French class where I met Joan again. I

knew her slightly at the Civil Service Tennis Club but, as I was a

fairly good tennis player, playing on the team, we were not really in

the same circle. However, we got on very well at the class and gradually

fell in love. I asked her to marry me while I was staying at her house

one weekend, and was very happy when she said "Yes". I bought

a house in Earlswood Park at the beginning of 1952, and we decided to

get married in April. As far as I remember, Joan would have liked a June

wedding, but as I had bought the house I could not wait so long. In

addition, by marrying on the last day of the income tax year (5 April),

I was able to reclaim the tax paid for the year, £40, which paid for

our honeymoon around Ireland. Joan's father kindly lent us his car for

the trip, as I had not a car at the time.

We were married on 5 April in Fortwilliam Presbyterian Church, Belfast,

with a reception in the Midland Hotel. On our way round Ireland we

stopped at Ballymiscanlon, Dublin, Waterford, Cork, Killarney, Galway

and Sligo and finally ended up in Dunkineely, before returning to

Belfast.

Our house in Earlswood Park was detached and had a small garden, which

was as much as I wanted. It was also a convenient distance from the

office which at that time was situated at Netherleigh in the grounds of

Campbell College and not far from Stormont.

About a year after our marriage, sadly Joan's mother died from lung

cancer and her father came to live with us. My own mother died in

December 1962 unexpectedly at the age of 74. This hastened my father's

death at the age of 85 in July 1963. Joan's father died in August 1964

at the age of 70. My brother died at the early age of 56 in 1969.

In the 1960s the political situation in Northern Ireland became very

difficult as the Nationalists were very aggrieved about their treatment

by the Unionist Government in regard to housing and jobs.

The IRA became a very strong organisation with the help of funds

from Irish patriots in America. The

bombings and killings went on for about thirty years.

Most of the fighting took place in West Belfast.

We lived in East Belfast near Stormont and as the great majority

of the people in that area

were descended from Scots and English we did not experience too much

trouble.

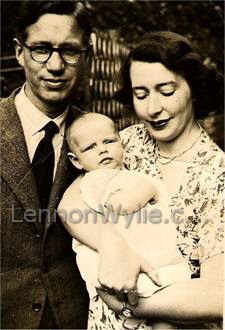

We were overjoyed

when Hilary was born in March 1953.

She was

a lovely child and brought us great joy. Then Alison arrived in February

1956 to complete our family and brought us further happiness. I am glad

to say they got on very well together and Hilary looked after her

younger sister very well.

At that

time our summer holidays consisted of visits to my parents in County

Donegal where we were able to enjoy the seaside.

Our

church in Belfast was St, Mark's, Dundela, which we attended regularly

and took part in many of the parish activities.

I was a member of the visiting team, each of whom had a number of

families to visit on a regular basis.

I

continued to attend my Masonic Mother Lodge but in 1958 I transferred to

an ex-Service Lodge called the Belfast Volunteers Masonic Lodge which,

of course, consisted of brethren who had served in the first and second

World Wars. It was an

excellent Lodge and we had many wonderful characters from the 1914-18

war.

During

the fifties I am afraid I did not play a great part in the upbringing of

our two daughters owing to my indifferent health.

It is greatly to Joan's credit that she brought them up so well.

It was in April 1959 when I fell ill again with tuberculosis and

spent eight months in Forster Green Hospital, where I recovered

reasonably quickly owing to the improved treatment which had recently

been discovered. That summer

Joan had to take the family on holiday to Donegal as she had then

learned to drive. She also

had to cope with a teenage French boy, the son of a French lady whom I

had met during the war. It

was good that she was able to manage all this without my help. During

the fifties I am afraid I did not play a great part in the upbringing of

our two daughters owing to my indifferent health.

It is greatly to Joan's credit that she brought them up so well.

It was in April 1959 when I fell ill again with tuberculosis and

spent eight months in Forster Green Hospital, where I recovered

reasonably quickly owing to the improved treatment which had recently

been discovered. That summer

Joan had to take the family on holiday to Donegal as she had then

learned to drive. She also

had to cope with a teenage French boy, the son of a French lady whom I

had met during the war. It

was good that she was able to manage all this without my help.

I resumed work at the Ministry of Education after an absence of one

year. Fortunately I continued to receive my war pension awarded at the

onset of my illness in 1947.

During the sixties our social life was quite good.

We enjoyed playing bowls and the companionship connected with it.

We attended a number of Masonic

Ladies` Evenings which included enjoyable dinner-dances.

There were also many events organised by the Burma Star

Association.

I

am glad to say Hilary and Alison did not cause us much trouble when they

were growing up. They both worked hard at school and passed exams

without any trouble. However, Hilary left school before A levels, worked

in a bank for one year, but then decided she would like to become a

teacher. She went to Birmingham for an interview and was accepted for

the three year teaching course at the Birmingham College of Education.

On completion of the course she became a qualified teacher, which was

obviously her true vocation, and as I write she has now completed 36

years in the profession. I

am glad to say Hilary and Alison did not cause us much trouble when they

were growing up. They both worked hard at school and passed exams

without any trouble. However, Hilary left school before A levels, worked

in a bank for one year, but then decided she would like to become a

teacher. She went to Birmingham for an interview and was accepted for

the three year teaching course at the Birmingham College of Education.

On completion of the course she became a qualified teacher, which was

obviously her true vocation, and as I write she has now completed 36

years in the profession.

Alison

did very well at her A level exams and was accepted by Edinburgh

University for a four year course in Medieval English. She enjoyed her

time in Edinburgh and we visited her there a few times. At the end of

the course she gained a Second Class, Division I, Honours degree. We

attended the graduation ceremony, which we found very interesting and

enjoyable. She did a post-graduate course at Durham University, and I

regret we did not visit her there. She then got a job in the Atomic

Energy Authority and worked at Doonreay in the north of Scotland for a

few years. After that she was seconded to the office in the British

Embassy in Washington DC. During her time there we visited her for a

month in the Autumn of 1982, shortly after we came to live in England.

She had a lovely apartment in Arlington. She showed us around the

interesting places in Washington, including Capitol Hill where we

attended a session of the House of Representatives and the Supreme

Court. We made a week's tour of Virginia, visiting many interesting and

historic places:

Williamsburg, Jamestown, Alexandria, Richmond, Harpers Ferry (West

Virginia) , Chesapeake Bay, ending up in Yorktown, where George

Washington finally defeated the British Army, which ended British rule

over the thirteen original states. It was a wonderful historic tour.

When Alison returned to the UK after two and a half years in Washington

she worked in London and had a flat in north London, where we visited

her a number of times and did what we could to help her.

In 1974

I was very surprised when I received a letter from 10 Downing Street

offering me the award of the M.B.E. for my work in the Civil Service.

Joan has written an excellent account elsewhere of our wonderful

experience of the investiture at Buckingham Palace by Her Majesty the

Queen.

In 1982

we made the decision to move to England to be nearer to the girls.

We put our house on the market and it was sold within a few

weeks. In March we took the

car over to England and spent a few

weeks looking for a suitable home.

We decided we would like to live in a village and toured around

Derbyshire, Warwickshire and Oxfordshire, finishing up in

Northamptonshire, a county quite unknown to us.

We stopped in Towcester and found a house in the village of

Greens Norton, about two miles away, which we liked very much.

We made the decision

to purchase it and set the necessary machinery in motion.

We then returned to Belfast to

finalise the sale of our house and to set about the daunting task of

clearing out the accumulated possessions of thirty years of family life.

When this was accomplished we

had to say Goodbye to a number of good, kind friends and relatives and

then set sail to begin the next phase of our lives.

I was then nearly 66 and Joan 58.

We moved to Greens Norton, in May 1982.

Although we did not know anyone, we found the village a very pleasant

place to live in. On our first Sunday here we went to the local church,

but hardly anyone spoke to us. However, I must say the rector was very

friendly and invited us to the rectory for afternoon tea. Then in 1983

the Fifty Plus Club was formed, which was wonderful for us as we were

then able to make many friends. We had a large number of activities, 14

in all, including Rambling, Table Tennis, French and Spanish classes,

Painting, Wine Circle and Musical Evenings. The Towcester and District

History Society had also been founded about that time, which, of course,

I joined and found it very interesting.

I missed my Freemasonry very much but was reluctant to join an English

Lodge as I knew their ritual was rather different from that practised in

Irish Freemasonry. However, when I started attending Burma Star dinners

in London I met a former member of our regiment, who belonged to the

Ulster Masonic Lodge. He persuaded me to join in 1989 and I became

Worshipful Master in the year 2000. The travelling to London was not

very convenient but I enjoyed the meetings.

Then in 1992 I joined the Lodge of Fidelity in Towcester and have

enjoyed the fellowship there very much indeed. In 1997 I was presented

with a certificate to mark my fifty years in Freemasonry, and a few

weeks ago (February 2007) I was very pleased to receive a sixty years

certificate.

In

October 1982 we were delighted to attend Hilary's wedding to Bryn in

Birmingham. It was indeed a very happy day for Joan and me and we were

very glad to welcome Bryn into our family. I think the arrival of our

grandson, Tom, about three years later, was the next big event in our

lives. Then, three years later we were again delighted when Caitlin was

born. In

October 1982 we were delighted to attend Hilary's wedding to Bryn in

Birmingham. It was indeed a very happy day for Joan and me and we were

very glad to welcome Bryn into our family. I think the arrival of our

grandson, Tom, about three years later, was the next big event in our

lives. Then, three years later we were again delighted when Caitlin was

born.

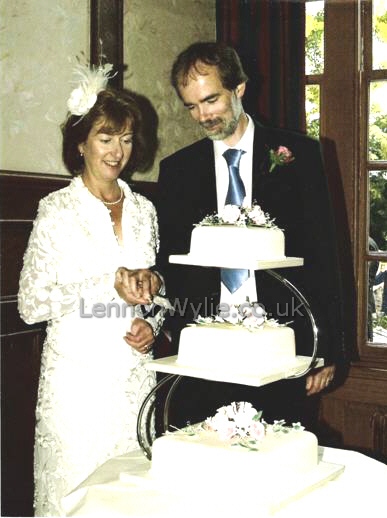

Our

family was further increased in September 2005 when Alison and Simon

were married in Abingdon and now live in Oxford.

Their wedding day was an extremely happy occasion ; we think very

highly of Simon and he has proved to be a wonderfully supportive husband

to Alison through her recent illness.

We are so thankful that both our daughters have found such good

men as their partners. Our

family was further increased in September 2005 when Alison and Simon

were married in Abingdon and now live in Oxford.

Their wedding day was an extremely happy occasion ; we think very

highly of Simon and he has proved to be a wonderfully supportive husband

to Alison through her recent illness.

We are so thankful that both our daughters have found such good

men as their partners.

Thinking of anniversaries, I should mention that we had a party in

Towcester for my seventieth birthday in 1986, and another for my

eightieth birthday, when we celebrated by having a conservatory added to

our house. When I reached my ninetieth birthday, in August 2006, we held

another large party in the new Community Centre in the village, attended

by sixty guests. All our family helped us very much in organising this

and we were very proud to have them all around us.

In May 2007 Hilary

suggested that we might like to move to be nearer to them and she and

Bryn started looking at retirement homes around Redditch.

It did not take us long to decide that we would like

to live in Cypress Grange, College Road, Bromsgrove, only about

six miles from Redditch. We

entered into negotiations to

do a “part exchange” with the owners of the complex for our house in

Greens Norton; they offered us a good price for it which meant

we did not have the worry and trouble of selling the house

ourselves.

We moved in to our apartment in July 2007, which I must say we could not

have managed without the tremendous help we received from Hilary and

Bryn. We appreciate very

much all the trouble they went to on our behalf.

We have settled into our new life here very happily and have made

many friends amongst the other residents, who are all very congenial.

We do miss our old friends in Greens Norton but we have been back

a few times to see them. I

have joined a number of organisations here including the British Legion,

the Burma Star Association, the Bromsgrove Twinning Association which is

twinned with towns in France, Germany and Italy.

I have also joined the University of the Third Age and enjoy

their meetings very much.

I feel it is now

time to bring these memoirs to a close as I am

approaching my 94th birthday.

I consider that I have been very fortunate to have been blessed

with so many years without coming to any harm.

-----------------------------------------------------------

APPENDIX

As most people who do not live in Ireland know very little about what

has happened there since the First World War, I feel I should explain

the situation as I see it.

When I was born in County Donegal in 1916 I became a citizen of the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

However, after that war the IRA began their fight for their

independence from Britain by attacking the Police and the British Army.

As my father was descended from the Scottish settlers, and a

Protestant, he also became a target of the IRA.

As a child, I remember the IRA attacking

our home and my father's business, from which they took a lot of goods.

They also tried to burn the front door down.

On one occasion they made my father transport them in his car to

their secret meeting in the hills outside our village.

He was very lucky they did not shoot him, which was the fate of

many Protestants at that time.

After peace was restored and Southern Ireland gained their independence

my father was very disappointed that County Donegal was not included

in the State of Northern Ireland, which chose to remain in the

United Kingdom. Donegal was

one of the original nine counties of Ulster.

However, as the Protestants of British

descent formed only 20% - 25%

of the population, it would not have been practical to include the

County in Northern Ireland.

After peace was declared in 1922, life for us was very pleasant.

We got on well with our

Roman Catholic neighbours, but of course the religious barrier caused

problems from time to time. I was fortunate to benefit from a

Grammar School education in Sligo and Dublin, but as I was brought up to

regard myself as British I moved to Northern Ireland and joined the

Northern Ireland Civil Service in 1935.

When war was threatened early in 1939 I had no hesitation in

joining a Belfast Territorial Regiment (although there was no

conscription in Northern Ireland) and

was glad of the opportunity to

serve my country throughout the war.

|